|

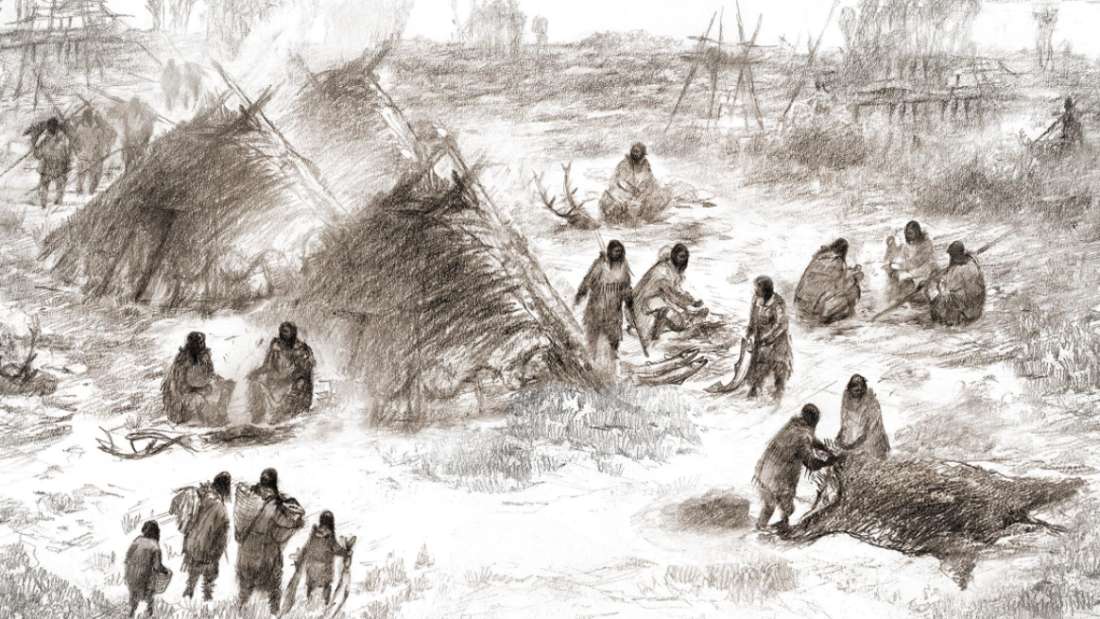

| An illustration of the Upward Sun River camp in what is now Interior Alaska. Illustration: Illustration by Eric S. Carlson in collaboration with Ben A. Potter |

Researchers have managed to sequence the genome of an ancient child that was descended from one of the original founding humans to have stepped foot in the Americas. A baby girl who lived and died in what is now Alaska at the end of the last ice age belonged to a previously unknown group of ancient Native Americans, according to DNA recovered from her bones. The child, a mere six weeks old when she died, was found in a burial pit next to the remains of a stillborn baby, perhaps a first cousin, during excavations of an 11,500-year-old residential camp in Tanana River Valley in Central Alaska. The remains were discovered in 2013, but a full genetic analysis has not been possible until now. Researchers tried to recover ancient DNA from both of the infants but succeeded only in the case of the larger individual. They had expected her genetic material to resemble modern northern or southern lineages of Native Americans, but found instead that she had a distinct genetic makeup that made her a member of a separate population.

The history of ancient humans in the Americas has always been somewhat obscure. Obviously, Native Americans have been present in the continent for thousands of years, and genetic evidence shows that they likely descended from humans who once lived in Eastern Asia and Siberia around 20-30,000 years ago. But there is scant physical evidence to support many of these theories, and the archaeological evidence that does exist is often confusing. For example, there are sites dated to around 13,000 years old in the north east of the Americas where many think the first humans to populate the continent would have first occurred, but there are also sites dating to around 15,000 years old in South America, thousands of kilometers away. This has tended to confuse the picture of human migration.

The most commonly accepted theory is that the peopling of America occurred during the Pleistocene, when the sea levels were lower and the Beringia land bridge connected Asia and North America. It is generally thought that by 11,000 years ago, after the Last Glacial Maximum, the land bridge was once again submerged and the two landmasses were separated. The genetic evidence now retrieved from Alaska backs this up, implying that when Beringia was still high and dry, a population of ancient humans originally from Siberia moved into the land. These people then became largely genetically isolated as the Ancient Beringians, before then moving across the bridge into the Americas. The land bridge then sank beneath the waves and the first Americans were cut off, though perhaps other peoples may occasionally have turned up by boat. |

| The team actually found the remains of two infants, but could sequence the entire genome of only one. Ben Potter |

But there is another possibility. Ben Potter, an archaeologist on the team from the University of Alaska in Fairbanks, suspects that the Beringians split from the ancestors of other Native Americans in Asia before both groups made their way across the land bridge to North America in separate migrations. “The support for this scenario is pretty strong,” he said. “We have no evidence of people in the Beringia region 20,000 years ago.” The families who lived at the ancient camp may have spent months there, Potter said. Excavations at the site, known as Upward Sun River, have revealed at least three tent structures that would have provided shelter.

The two babies were found in a burial pit beneath a hearth where families cooked salmon caught in the local river. The cremated remains of a third child, who died at the age of three, were found on top of the hearth at the abandoned camp. Connie Mulligan, an anthropologist at the University of Florida, said the findings pointed to a single migration of people from Asia to the New World, but said other questions remained. “How did people move so quickly to the southernmost point of South America and settle two continents that span a huge climatic and geographic range?” she said. David Reich, a geneticist at Harvard University, said the work boosted the case for a single migration into Alaska, but did not rule out alternatives involving multiple waves of migration.

He added that he was unconvinced that the ancient Beringian group split from the ancestors of other Native Americans 20,000 years ago, because even tiny errors in scientists’ data can lead to radically different split times for evolutionary lineages. “While the 19,000-21,000 year date would have important implications if true and may very well be right, I am not convinced that there is compelling evidence that the initial split date is that old,” he said.

The child, a mere six weeks old when she died, was found in a burial pit next to the remains of a stillborn baby, perhaps a first cousin, during excavations of an 11,500-year-old residential camp in Tanana River Valley in Central Alaska. The remains were discovered in 2013, but a full genetic analysis has not been possible until now.

Researchers tried to recover ancient DNA from both of the infants but succeeded only in the case of the larger individual. They had expected her genetic material to resemble modern northern or southern lineages of Native Americans, but found instead that she had a distinct genetic makeup that made her a member of a separate population.

No comments:

Post a Comment